A wealth of human history lies submerged in ancient cities at the bottoms of lakes, seas and oceans of the world. Some of these were sent into the water via earthquakes, tsunamis or other disasters thousands of years ago. Many have just recently been rediscovered, by accident or through emergent technological innovations. Some have even caused scientists to question the history of human civilization.

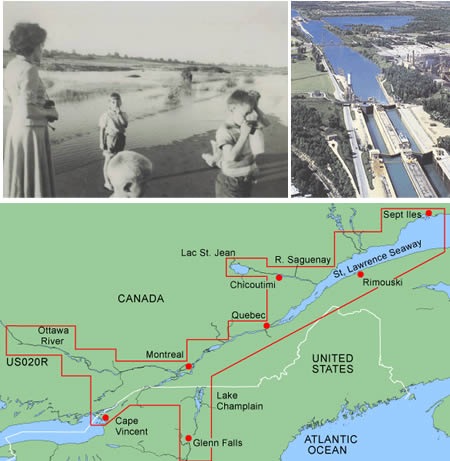

7. The Lost Villages (Canada)

"The Lost Villages" are ten communities in the Canadian province of Ontario, in the former townships of Cornwall and Osnabruck (now South Stormont) near Cornwall, which were permanently submerged by the creation of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1958.

The flooding was expected and planned for. In the weeks and months leading up to the inundation, families and businesses in the affected communities were moved to the new planned communities of Long Sault and Ingleside. These negotiations were controversial, however, as many residents of the communities felt that market value compensation was insufficient since the Seaway plan had already depressed property values in the region.

The town of Iroquois was also flooded, but was relocated 1.5 kilometres north rather than abandoned. Another community, Morrisburg, was partially submerged as well, but the area to be flooded was moved to higher ground within the same townsite. A portion of the provincial Highway 2 in the area was flooded; the highway was rebuilt along a Canadian National Railway right-of-way in the area.

At 8 a.m. on July 1, 1958, a large cofferdam was demolished, allowing the flooding to begin. Four days later, all of the former townsites were fully underwater. Parts of the New York shoreline were flooded by the project as well, but no communities were lost on the American side of the river.

In some locations, a few remnants of sidewalks and building foundations can still be seen under the water, or even on the shoreline when water levels are sufficiently low. Some high points of land in the flooded area remained above water as islands, and are connected by the Long Sault Parkway. Lock 21 of the former Cornwall Canal (since replaced by the Saint Lawrence Seaway) is a popular scuba diving site, a few feet from the shore along the Parkway.

6. Dwarka Port (India)

Among the most exciting archaeological discoveries made in India in recent years are those made off the coast of Dwarka and Bet Dwarka in Gujarat. Excavations have been going on since 1983. These two places are 30 km away from each other. Dwarka is on the Arabian sea coast, and Bet Dwarka is in the Gulf of Kutch. Both these places are connected with legends about the good Krishna and there are many temples here, mostly belonging to the medieval period.

Rated as one of the seven most ancient cities in the country, the legendary city of Dvaraka was the dwelling place of Lord Krishna. It is believed that due to damage and destruction by the sea, Dvaraka has submerged six times and modern day Dwarka is the 7th such city to be built in the area.

Archaeologists were keen to find out whether there were any older remains off the coast at these places.

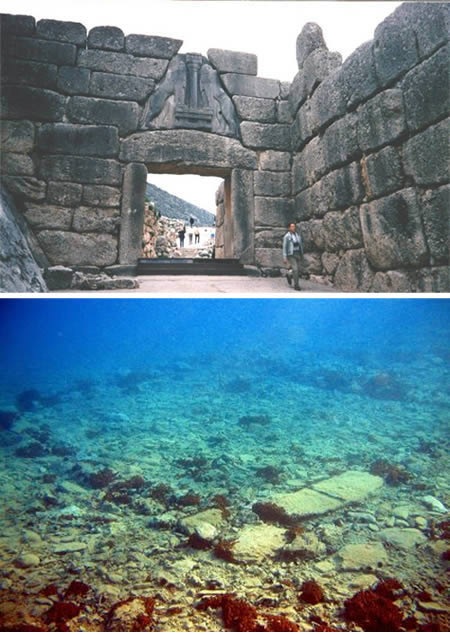

5. Pavlopetri (Greece)

The ancient town of Pavlopetri lies in three to four metres of water just off the coast of southern Laconia in Greece. The ruins date from at least 2800 BC through to intact buildings, courtyards, streets, chamber tombs and some thirty-seven cist graves which are thought to belong to the Mycenaean period (c.1680-1180 BC). This Bronze Age phase of Greece provides the historical setting for much Ancient Greek literature and myth, including Homer's Age of Heroes.

Although Mycenaean power was largely based on their control of the sea, little is known about the workings of the harbour towns of the period as archaeology to date has focused on the better known inland palaces and citadels. Pavlopetri was presumably once a thriving harbour town where the inhabitants conducted local and long distance trade throughout the Mediterranean — its sandy and well-protected bay would have been ideal for beaching Bronze Age ships. As such the site offers major new insights into the workings of Mycenaean society.

Underwater archaeologist Dr Jon Henderson, from The University of Nottingham, is the first archaeologist to have official access to the site in 40 years. Despite its potential international importance no work has been carried out at the site since it was first mapped in 1968 and Dr Henderson has had to get special permission from the Greek government to examine the submerged town. According to him, this site is of rare international archaeological importance. It is imperative that the fragile remains of this town are accurately recorded and preserved before they are lost forever.

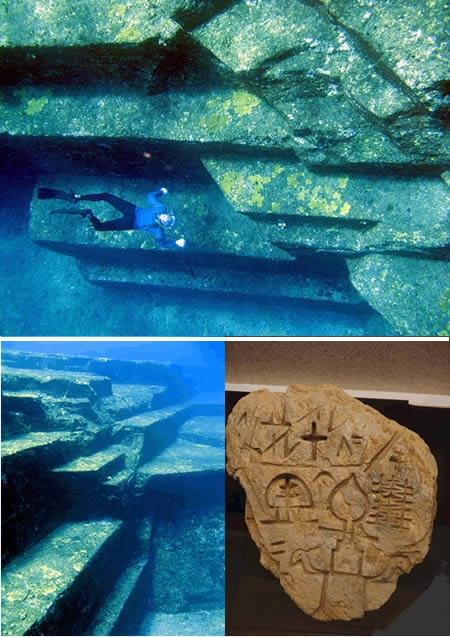

4. 8000-year-old Yonaguni-Jima (Japan)

Situated 68 miles beyond the east coast of Taiwan, Yonaguni Islands are a remarkable place for its rugged and mountainous coastlines. The special attraction is the submerged ruins located in the southern coast of Yonaguni: a superb 100×50x25 meters man-made artifact out of solid rock slabs stands erect at right angles. Its is estimated to be around 8000 years old, which is remarkably early for the kind of technology that has been used for carving it. Different theories exist about the possible identities of this structure.

While some say these ruins are the remnants of the missing Continent of Mu, other archeologists attribute them to be the outcome of unexplained geological processes, although, when you see the finely designed hallways and staircases, this ‘natural phenomenon' idea will appear sheer out of place.

The megalith was discovered quite accidentally by a sport diver in 1995 when he had strayed beyond the permissible limit off the Okinawa shore. The interesting thing about this massive stone building is that it had arches made of beautifully fitted stone blocks bearing resemblance with the building architectural style of the Inca civilization. Debates were rife about the ruins being associated with the prehistoric Motherland of Civilization. Surveying the ruins minutely takes time and skill because of the rough oceanic currents. (Link | Photo 1 | Photo 2 | Photo 3)

3.The submerged temples of Mahabalipuram (India)

According to popular belief, the famous Shore Temple at Mahabalipuram wasn't a single temple, but the last of a series of seven temples, six of which had submerged. New finds suggest that there may be some truth to the story. A major discovery of submerged ruins was made in April of 2002 offshore of Mahabalipuram in Tamil Nadu, South India. The discovery, at depths of 5 to 7 meters (15 to 21 feet) was made by a joint team from the Dorset based Scientific Exploration Society (SES) and marine archaeologists from India's National Institute of Oceanography (NIO). Investigations at each of the locations revealed stone masonry, remains of walls, square rock cut remains, scattered square and rectangular stone blocks and a big platform with steps leading to it. All these lay amidst the locally occurring geological formations of rocks.

Based on what at first sight appears to be a lion figure at location four, the ruins were inferred to be part of a temple complex. The Pallava dynasty, which ruled the region during the 7th century AD, was known to have constructed many such rock-cut, structural temples in Mahabalipuram and Kanchipuram.

2. World's Wickedest City, Port Royal (Jamaica)

One of the advantages of marine or nautical archeology is that, in many instances, catastrophic events send a ship or its cargo to the bottom, freezing a moment in time. A catastrophe that has helped nautical archeologists was the earthquake that destroyed part of the city of Port Royal, Jamaica. Once known as the "Wickedest City on Earth" for its sheer concentration of pirates, prostitutes and rum, Port Royal is now famous for another reason: "It is the only sunk city in the New World," according to Donny L. Hamilton.

Port Royal began its watery journey to the Academy Awards of nautical archeology on the morning of June 7, 1692, when, in a matter of minutes, a massive earthquake sent nearly 33 acres of the city -- buildings, streets, houses, and their contents and occupants -- careening into Kingston Harbor. Today, that underwater metropolis encompasses roughly 13 acres, at depths ranging from a few inches to 40 feet.

In 1981, the Nautical Archaeology Program of Texas A&M University, in cooperation with the Institute of Nautical Archaeology (INA) and the Jamaica National Heritage Trust (JNHT), began underwater archaeological investigations of the submerged portion of the 17th-century town of Port Royal, Jamaica. Present evidence indicates that while the areas of Port Royal that lay along the edge of the harbor slid and jumbled as they sank, destroying most of the archaeological context, the area investigated by TAMU / INA, located some distance from the harbor, sank vertically, with minimal horizontal disturbance.

In contrast to many archaeological sites, the investigation of Port Royal yielded much more than simply trash and discarded items. An unusually large amount of perishable, organic artifacts were recovered, preserved in the oxygen-depleted underwater environment. Together with the vast treasury of complimentary historical documents, the underwater excavations of Port Royal have allowed for a detailed reconstruction of everyday life in an English colonial port city of the late 17th century. (Link 1 | Link 2)

1. Cleopatra's Palace in Alexandria (Egypt)

Off the shores of Alexandria, the city of Alexander the Great, lies what is believed to be the ruins of the royal quarters of Cleopatra. A team of marine archaeologists led by Frenchman Franck Goddio made excavations on this ancient city from where Cleopatra, the last queen of the Ptolemies, ruled Egypt. Historians believe this site was submerged by earthquakes and tidal waves more than 1,600 years ago.

The excavations concentrated on the submerged island of Antirhodus. Cleopatra is said to have had a palace there. Other discoveries include a well-preserved shipwreck and red granite columns with Greek inscriptions. Two statues were also found and were lifted out of the harbour. One was a priest of the goddess Isis; the other a sphinx whose face is said to represent Cleopatra's father, King Ptolemy XII. The artifacts were returned to their silent, because the Egyptian Government says it wants to leave most of them in place to create an underwater museum